Sherryl Clark’s literary career is what might be called a trans-Tasman one; born and brought up in New Zealand, but living in Australia for many years, she is well-known in both Australia and New Zealand for the versatility and quality of her books, which range over many genres and age ranges. Today I talk to her about what it means to straddle those national cultures, and those different types of literature–as well as teaching literature, undertaking literary degrees, and lots more!

Sherryl Clark’s literary career is what might be called a trans-Tasman one; born and brought up in New Zealand, but living in Australia for many years, she is well-known in both Australia and New Zealand for the versatility and quality of her books, which range over many genres and age ranges. Today I talk to her about what it means to straddle those national cultures, and those different types of literature–as well as teaching literature, undertaking literary degrees, and lots more!

********************

Sherryl, you grew up in New Zealand but now live in Australia. Do you consider yourself an Australian or New Zealand writer, or both? And what similarities and differences do you think there are in terms of the literary world of each country?

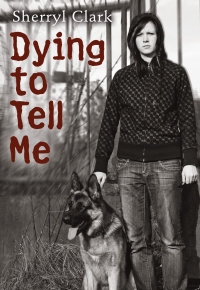

I’ve now lived in Australia for 37 years, but I think in my heart I am still a New Zealander, especially because I grew up on a farm and I think your first 18 years ‘imprint’ you. However I do think my stories are Australian, funnily enough, with some New Zealand elements. If I write about a farm (as in Farm Kid), it’s an Australian farm with drought and brown paddocks which you just don’t see in NZ like that. Not where I come from anyway. Dying to Tell Me is definitely Australian bush, and even my city stories, whether historical or contemporary, are very much set in Melbourne. I feel for NZ writers today – the publishing opportunities have narrowed so much. But at the same time I think many NZ writers are writing with real passion about their country, in very particular ways, and I don’t see that nearly so much in Australia.

You have written many children’s books in different genres, and for different age groups. Is there an age group/genre you most enjoy writing for, and why? Is there a book of yours that you think of particularly fondly? And how has what you write about changed over the years? (if indeed it has!)

I love picture books because of the process – the challenge of so few words – and the amazing work that illustrators do. I love verse novels because I love how poetry expresses things that prose struggles with. I think my favourite age group to write for is 11-14. To me it’s a time when you become aware of the outside world, of what people are like, the value of friends, the idea of adventure and exploration – the whole world opens up, but at the same time it’s when the whole world can make your life very hard. Anything can happen and bad things do. To me, writing about those things is a way to tell kids they’re not alone, and I think that’s important. I agree with Neil Gaiman – kids need to believe they can be brave and win against the dragons. I think that’s why I like Dying to Tell Me, my murder mystery for upper middle grade readers. Sasha has made some stupid choices without understanding why, but now she learns to be brave and to use her wits. I think my writing has become braver, too! I turned a corner about four years ago, during the MFA, when I realised that I just had to start writing what really stirred me and obsessed me, and stop worrying about what might come after.

I love picture books because of the process – the challenge of so few words – and the amazing work that illustrators do. I love verse novels because I love how poetry expresses things that prose struggles with. I think my favourite age group to write for is 11-14. To me it’s a time when you become aware of the outside world, of what people are like, the value of friends, the idea of adventure and exploration – the whole world opens up, but at the same time it’s when the whole world can make your life very hard. Anything can happen and bad things do. To me, writing about those things is a way to tell kids they’re not alone, and I think that’s important. I agree with Neil Gaiman – kids need to believe they can be brave and win against the dragons. I think that’s why I like Dying to Tell Me, my murder mystery for upper middle grade readers. Sasha has made some stupid choices without understanding why, but now she learns to be brave and to use her wits. I think my writing has become braver, too! I turned a corner about four years ago, during the MFA, when I realised that I just had to start writing what really stirred me and obsessed me, and stop worrying about what might come after.

What’s your latest book, and what are you working on now?

My latest book/s are a series based on Ellyse Perry (sportswoman). It was a commission, and I wanted to do it because I hated compulsory sport at high school, and so did lots of other girls. And I see someone like Ellyse being a huge influence on kids and getting them away from screens and participating in sports – and having fun. I wish that had been me! Plus adolescence and body changes have a lot to do with why girls stop playing sport and I wanted to explore that, too. I also have a picture book coming out next year with Allen & Unwin – The Night Tiger – which is being illustrated by Michael Camilleri. I’m very excited about that.

I’m always working on several things, so I can give manuscripts a ‘rest’ when they need some time out, so I’m able to able to look at them with a fresh eye. I’ve just finished a major revision of a SF novel (the ending still needs more work), and I’m doing another edit of a historical novel. I changed a large part of it into present tense and it’s still a bit clunky.

You’ve written poetry for both children and adults, and have edited a poetry magazine, Poetrix. Can you tell me something about both your poetry, and the magazine?

Poetry was the first thing I wrote when I realised what writing was. That probably sounds weird, but I’d been writing these dull short stories and an awful adult novel, and then I did a poetry workshop and thought – yes! I wrote this thing and the workshop leader said it was a nice metaphor and then I thought – what’s a metaphor? And since then (30 years ago, mind you!) I’ve been learning more and writing more, and it’s such an exploration of language and image. So much fun and so satisfying, and I just wish more schools would ask for poetry workshops. Truly. Most teachers have NO idea what poetry can open up for kids. And most importantly for those kids who don’t feel confident with language and prose. Poetry just excites them so much. They are the BEST poets!

We created Poetrix (Australia’s only magazine for women poets) back in 1993. I used to teach classes in self-publishing because it was a passion of mine, and I’d worked in community arts and for a printer. My writing group, Western Women Writers, were totally on board with creating a magazine, and we self-funded it with small catering jobs. We produced 40 issues of Poetrix, and we published a huge number of women who have gone on to have books published and won awards. But mostly we did it so women had a poetry voice. It was in reaction to some critic who’d said women only wrote poetry that was ‘domestic suburban vignettes’ and we thought – yes? So what’s wrong with that? It’s life as we know it and experience it, and of course you can write fabulous poems about it! So here are 40 issues of Poetrix and about 1400 poems about things that are important to us. To everyone, actually.

As well as writing books, over the years you’ve also run a lot of classes on writing and publishing. What kinds of things do you most enjoy helping people to learn? Do you teach mainly children, or adults, or a combination? And do you think that things have changed in terms of areas of interest–I mean, are people interested in learning about different things now than they were say 10 or 15 years ago?

I’ve been teaching in the Diploma and Cert IV of Professional Writing and Editing for nearly 20 years. But I did get to a point finally where I realised how much energy and focus teaching was sucking out of my writing. I went off to Hamline University in Minneapolis to do an MFA in writing for children and YA, and a very wise teacher there said, ‘It all comes from the same well. The more you teach, the less you have for your own writing.’ So in the past three years I have stopped teaching at TAFE, apart from substituting and helping out, and I think my own writing has received a huge boost because of that. It’s sad to say this, but it’s true. Teaching did detract from the energy I had for writing, and now with the whole onslaught of government paperwork requirements, more and more writing teachers are leaving TAFE because it’s overwhelming. Less time to teach and more time to fill out pointless forms. It makes me angry, to be honest.

Because I do love teaching and workshops. The people who come are so keen to write, and to learn. You can feel them soaking stuff up. I often see people start with an introductory class and five or ten years later, they’re getting published and doing so well. The one thing I love teaching is story structure. People get so mired in character and dialogue and just getting the words out, but structure (if you learn it and understand it) can fix just about everything. Mind you, it can’t fix voice, and in writing for children and YA, voice is so important. I think you only ‘get’ voice if you read a lot, read widely and read from a writer’s viewpoint. It astounds me when aspiring writers say they don’t read. There is so much to learn from astute reading.

I teach mainly adults still – I do writing workshops in schools, yes, but a lot of schools want to spread their resources as widely as possible, of course, so I will do talks to 300+ students rather than workshops with 20. My dream is to create a portable poetry workshop I can take to school teachers and show them how to use poetry in the classroom, both reading and writing it. I have a website I started back in 2006 when I realised how little there was for schools – www.poetry4kids.net. I need to update it now and put a lot more material on it.

At the moment, you are undertaking a PHD themed around fairy tales, through an Australian university, after doing a Master of Fine Arts degree through an American university. What was your main focus in the MFA? What aspect of fairytales are you focussing on in the PHD? And how do the two university cultures compare?

When I chose to do the MFA in the US, it was because I knew it was the only way to do a Masters in the way I wanted. I didn’t want to be stuck doing one topic and one novel with one or two supervisors. Hamline meant I could do the things I really wanted: work with a different advisor every semester and learn from them (all published, experienced writers and teachers); work on a different project every semester to learn as much as possible (so I did a historical novel, picture books, a verse novel and a SF novel, plus a critical thesis on verse novels); go to intensive residencies in Minneapolis/St Paul where there were lectures, readings, workshops and a committed community of children’s writers; work at home via email in between and get detailed feedback on my writing; learn to write critical essays and a thesis that taught me more about the field from a critical viewpoint.

The PhD at Victoria University in Melbourne came from an essay I wrote during my picture book semester at Hamline. It was about picture books that are original, new fairy tales (Fox by Margaret Wild was my key text). Now my PhD asks that question – if I want to write new, original fairy tales myself, how do I achieve this? How do I write something that has the same resonance and unconscious signals that traditional tales like the Grimms’ do? So the creative writing (picture books and a novel) is informed by the research. Why have fairy tales endured? What is it that we respond to? How can I use this without being prescriptive or didactic or just plain boring?

Of course other aspects have come into it, especially the issue of publishers avoiding scary stories, and over-protective parenting that leads to a lack of resilience and coping skills in kids. I didn’t intend to venture into psychology, but then given that Bettelheim’s book, The uses of enchantment, was my starting point, I guess it was inevitable!

The two universities are poles apart, but that’s to be expected. Any Australian university would be entirely different to a US university that both specializes in children’s/YA writing and offers a low residency option. I think perhaps we’re not big enough here to be able to either specialize in that way or offer low residency on a wide scale. I’ve approached VU about running an MA similar to Hamline (indeed Hamline are keen to form a partnership), but with the government continually cutting tertiary funding and clearly having such an anti-arts agenda, I can’t see it happening anytime soon.

I think it’s so interesting that so many writers now are doing PhDs, because you can apply for a scholarship and it gives you an incredible amount of time to focus and create and innovate. Funded time that you don’t get hardly any other way. My bet is that in the next 10-15 years, Australian writing will see a huge growth in quality and innovation because of it. But if the government gets its scaly, arts-hating hands on the PhD program funding, they will kill it. Maybe I shouldn’t be telling them? Ssshhh.

Sherryl Clark’s first children’s book, The Too-Tight Tutu, was published in 1997, and she now has more than 65 published books. Her other titles include a number of Aussie Bites, Nibbles and Chomps, and novels. Her YA novels are Bone Song, published in the UK in 2009, and Dying to Tell Me (KaneMiller US 2011, Australia 2014).

Sherryl’s verse novel Farm Kid won the 2005 NSW Premier’s Literary Award for children’s books, and her second verse novel, Sixth Grade Style Queen (Not!) was an Honour Book in the 2008 CBCA Awards. Other recent titles include a picture book of poems, Now I Am Bigger, the middle grade novel Pirate X and the Rose series (Our Australian Girl). Her fourth verse novel, Runaways, was released March 2013.

Her latest books are the series featuring sportswoman Ellyse Perry. Pocket Rocket and Magic Feet are released in early October, with two more in January 2017.

Her books have been published in Australia and overseas, including the USA, UK, Spain, Mexico and China.

Her website is at www.sherrylclark.com

Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/Sherryl.Clark3

Twitter – @sherrylwriter

Instagram – sherrylwriter