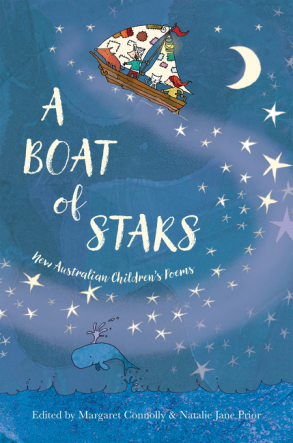

I wrote this story, ‘The Other Anzac Day’ for a 2014 UK anthology for middle-grade/YA readers, Stories of World War One, edited by fabulous British author Tony Bradman and published by Orchard Books. Set in Villers-Bretonneux in France in April 1918–in fact on Anzac Day 1918–it’s told in the voice of a young Australian soldier, Archie Bell, and though some of the other named characters come from my 2011 middle-grade novel, My Father’s War, it’s a completely standalone story. It’s both for young readers, and readers of all ages. It’s a story that I found both easy to write–in that it flowed incredibly naturally–and hard to write–in that it made me weep as I wrote it. And it’s one I’m still proud of, that I wouldn’t change a word in…

Anyway, here it is, for Anzac Day.

The Other Anzac Day

by Sophie Masson

Villers-Bretonneux, France, April 1918

Like shadows in single file we move silent as snakes through the wood, slipping down the sunken roads to take our positions. All is quiet. The machine guns are silent, thank Christ. Fritz is sleeping. We hope. The Poms are somewhere out there moving towards the town, and on the other side of us somewhere are the other Aussies. It’s a pincer movement, Owl had said. He’s our resident professor. Reads all about military strategy for fun, draws little diagrams for us. See, here, that’s how it’ll be done, the Aussie battalions from the left and right, the Poms in the middle, no artillery attack first, right, just our weapons in hand, rifles and bayonets for most of us, machine guns for the gunners, total surprise. We knock out the machine gun nests, and we fall on Fritz before they even know we’re there. Like tigers in ambush, like wolves on the fold, says Pat, who’s something of a poet. Mate, says Snowy, snorting, them Boche aren’t what you’d call meek little lambs, they fight like demons and don’t you forget it.

There was a moon but the clouds have swallowed it up now. There’s a strange red light in the sky over the little town just past the wood and a smell that reminds me of last year when I was fighting that fire at the neighbour’s back home. Houses are burning in the town, shelling’s been going on for days and V-B is rubble and burning houses and smoking ruins now. But one old French bloke we spoke to the other day, old farmer who’s hung on and on like a tough tick on a cow, he told us that once the town was pretty and brisk as you please, a magnet for the little villages and farms around it, at least that’s what Owl said he said, and as he’s the only one of us who speaks proper Frog we got to trust him in that, hey? The town might be flattened but the fields around are full of grass and flowers growing over the deep scars of old trenches all over. There was a lot of trench fighting in this district before like in all of this Somme region but now that’s over. No animals of course right now but a few small crops starting to be planted. Looks like nice fertile country, you could get a mighty good yield here, my uncle back home would say.

It’s a different kind of war to before, no more trenches. In the past it was mud and trenches from end to end of the Somme. Men lived in trenches, died in them. Now it’s skirmishes and battles in woods and towns, more the sort like at the beginning of the war, Owl says. He says it’s changed again now cos there’s not so much a stalemate as before. The Yanks came in our side last year but there’s not enough of ‘em yet and now Jerry’s got the advantage. They’re stronger than for a long time. They’ve got lots of fresh new troops pouring in from the Eastern Front where the Russkies gave up fighting last year, and they’ve been launching lightning attacks all up and down the north of France and Belgium, pushing the Poms and the Frogs and us Colonials, Aussies and Canadians and New Zealanders, back and back.

That’s why we’re here cos earlier this month Fritz took Villers Bretonneux again, VB as we call it, and though it’s just a small town, it’s important. You have VB, you have a direct shelling line to the city of Amiens from the hill near here, Hill 104 they call it, and then there’s a Roman road straight as an arrow just right for an army to march right to the heart of that city once the way’s cleared. And from Amiens well you are not that far to Paris. It’s important not to lose Amiens. It’s important not to lose VB, no matter what, whatever it costs. And it’s cost plenty. The Poms took heavy heavy losses two weeks ago. Hundreds of the poor beggars killed and injured. That might happen to us today but you can’t think of that. You got to think, we got to take it back from Fritz. From Jerry. The Boche. Whatever you want to call them out there in the darkness, the Germans, dug into the town and the surrounding woods and countryside. They’re somewhere in here, with us. We got to find them before they find us…My hand tightens on my weapon. I’m ready for them. I’m more than ready..

‘Hey boys, it’s gone midnight,’ whispers Snowy. ‘It’s the 25th now. Anzac Day. ‘

‘Good omen, I reckon, ‘says Blue, and everyone nods.

‘Lest we forget,’ says Pat, and he says another few words, solemn-like, and for once no-one tells him to shut his trap. But forget? Not a chance. We’re all thinking of that very first Anzac Day. A surprise night attack, like this one. Gallipoli. The landing at the place we now call Anzac Cove. Three years to the day. Almost to the hour.

I remember the headlines in the newspapers the next day. Glorious Deeds! Unsurpassed Daring of the Anzacs! Miracle of Bravery! The day the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps really showed what we were capable of. When we wrote our new nations proudly into the roll call of glory. Australia and New Zealand’s baptism of fire, a day to remember forever.

I devoured every word. I was so proud. My older brother Jamie was in one of the Anzac battalions there. I could just picture him as I read how after being given a good hot meal and a drink on board their ships the Anzacs had landed on that beach in the dead of night—a clear bright moonlit night though, not like this one. Everyone was calm, ran the reports. Everyone was itching for battle but calm as you like. There were only whispers among the men, quiet footfalls, no loud noises. The Turks up on the heights were not expecting it. They were taken by surprise as up and down the coast the Allied forces—the French, the British, including the Anzacs, moved in by sea at night. But they soon recovered and the landing was soon raked by rifle and machine gun fire from the cliffs. In some of the landing places the cliffs could be scaled more easily but at Anzac Cove the cliffs were so sheer so steep that it proved almost impossible. Heavy casualties, reported the correspondents gravely, and there will be grief in many households, but such feats of incredible courage against great odds will give comfort.

I wish that had been true for my mother. Yet when she got the telegram that Jamie would not be coming home, that he had been killed at faraway Gallipoli, she did not cry. Did not scream, like the mother of Norm Penny, up the road. Her screams you could hear up and down the street. My mother said nothing. Sat in the chair with the telegram in her lap, staring into space. She sat like that for hours. Wouldn’t talk. Wouldn’t eat. Wouldn’t even take a cup of tea, she who lived on tea from morning till night. Strewth, I didn’t know what to do, so I went and fetched our next door neighbour Mrs Hunt who was good friends with Mum and who I thought might help. And she did, while sending me outside to chop up some firewood—you need to do something, love, she said, you’re all jumpy and you’re making it worse for her.

As I chopped and chopped, more wood than we’d use for weeks probably, though I was sweating from the effort, I could feel inside my throat something that sat like a hard cold lump. I knew what it was. I’d never see Jamie again. Never hear his laughing voice joshing me. Never have to put up with his calling me Kid Arch. Or Little Archie. Or Mini Bell. Six years older than me he was, and man of the house since Dad died when I was three. When I was real little I used to follow him around. Even after I stopped being his faithful dog, I liked being around him. He was a real good fella though he could be blanky irritating with those nicknames. I would miss him, I knew that. I’d miss him so bad. But I was also so proud of him. So proud. My brother. My only brother. He was a real honest to God hero. A hero of Anzac Cove.

I tried to say that to Mum, later. Much later. Maybe it was the wrong thing to say. Women don’t see things the way we do. I wasn’t trying to say that it didn’t matter Jamie was gone. It mattered terribly. There would always be that empty place in me that was the ache for him. But it made it better, to know he’d died a hero. When the next year they started the ceremonies, the marches, to remember that day, I went proudly to them. I felt a part of it in a way that I had never felt part of something before, even our local footy team. (No wonder, kid, Jamie would’ve joked, given your footy skills!) And even after I heard some people saying that the landing at Anzac Cove had been a mistake, that the generals had led our boys into slaughter, even then that didn’t change a thing for me. Being a hero isn’t about doing great things when you’re certain of winning. When the odds are good. When the stars are aligned. It’s not about the glory the papers wrote about either. It’s about doing the right thing by your mates. Even when death is staring you in the face. No, not even. Especially then.

That’s what Snowy says. And Snowy was there. Like Jamie. He didn’t know Jamie, he was in a different battalion. But he’s told me about it. Made me feel it. Understand it. See it. Feel it, in my bones. Snowy’s been a soldier a long time. Comes from near Beechworth way. Kelly country. (His old man knew the Kellys in fact). He’s survived several injuries. Badly wounded at Gallipoli. Invalided to Britain. And then straight back only a few weeks later. To Belgium this time. The trenches. Got gassed there, survived that, came back for more punishment. This is the second time he’s been on the Somme. All the others, too, they’ve been in this for a good while. Me, only two months. I couldn’t join up before, though I really wanted to. Yeah, so I was too young really, only thirteen when Jamie died, but it wasn’t that. I could’ve lied about my age. I’m big for my age, they say. Tall. Broad shoulders like me dad. Like Jamie. Can’t play footy to save me life but boxing, I’m pretty good at. Strong. Not scared of Jerry or anything. Wanted to fight. But I couldn’t. Not with Mum the way she was. She never got over Jamie. She had what the doctor called a breakdown. Couldn’t go to work no more. Never really recovered. I had to leave school and get a job in the timber-mill, not that I minded, never much liked school. And I had to take care of her. There was this strange thing she did, where she wanted me to read to her, from the newspapers. Though she could read perfectly well. She wanted me to read every scrap, the news, the weather report, the advertisements, every blanky thing. I didn’t want to at first because the papers were of course full of news of the war and I feared it might upset her even more. But if I tried to leave that out she got angry. She would listen to the account of the battles and not say a word. Sometimes I’d make some comment on the blanky Germans or Turks or whoever and she’d nod as if she agreed but I don’t think her mind was on it. I don’t know where her mind was to be honest. And when she died last year from a stroke, it was like what was started that day she got the telegram was finally ended. Like she’d been dying from that moment. Like it was almost a mercy. I went to the recruiting office the next week. Bumped my age up two years, told ’em I was eighteen. They didn’t ask too many questions. Embarked two weeks later. And so here I am now.

‘We’re goin’ forward.’ The word’s passed down the line. It’s on. Jerry can’t be far now, but still no artillery firing. Silently, we break off into three groups, a main body heading to the town, two on the flanks to protect us and mop up Fritz outposts before they give us too much grief. I’m in the main body close to Snowy, Blue and Owl are somewhere behind us with Jimbo their other friend and on the flanks, melting away into the darkness, Pat is with the ones who’ll be making the way safe for us. Or a little safer anyway.

Closer, and we can hear fighting now as Pat’s group and the others run into Fritz. We keep moving forward, bunching together because of the barbed wire fences that are everywhere, left behind by succeeding holders of the town, Fritz, the Frogs, the Poms, Fritz again, us, whoever. It’s like trying to fight your way through a giant spider’s web. Suddenly, a burst of flares. Red, green, white yellow. Someone says, and I think it’s Blue, ‘Hello, fireworks for Anzac Day, boys,’ and that raises a laugh. But of course we know it means Fritz has heard us. Seen us. We duck down, waiting for what must come next and right on cue it does, a storm of machine-gun fire from the right of us and in front. I’m running like the others, head down, trying not to get shot or entangled in the blanky barbed wire. Behind me I hear screams, looking back I see Blue and Owl have been hit and Jimbo’s trying to help them, but I can’t go back and help, now’s not the time, I’m in the heart of the mob of us, Snowy at my side. And all of us with our bayonets fixed to our rifles, yelling, snarling, howling like the demons of hell or the wolves and tigers Pat spoke of earlier, we charge at the Germans.

Faintly in the distance we hear cheers from the other side of the town and know that the other Aussie brigade has heard us. Straight at the Germans we charge, and so taken aback are they by this wild onslaught that they are slow to react and when they do it’ s too late. I can hardly describe what happens in the next half hour or so, no quarter given on our side or theirs. Fritz fights back bravely, gunners trying to fire even when they’re run through by bayonets like chickens on a spit. Sweat running down my face, I’m hardly Archie Bell from Castlemaine any more, but just part of a wild mob, parrying to left and right, trying to get in blows, to kill, to live, to win, to back up our mates. And then I get a Jerry, straight through the heart, a lucky blow, despite my wild thrust, and I see his eyes stare at me bewildered as he falls. His eyes are blue, the exact shade of Jamie’s, and though this is not the first time I have killed a man in battle it is the first time at such close quarters and for a heartbeat I feel that knowledge rise in my gorge like sick.

But there’s no time to think. Our rush has been so fast that we are too far in VB too soon and have to pull back a little. But the Germans in the town have seen what’s happened and from then on they start surrendering. Dozens of them, soon hundreds, so many prisoners that it becomes an embarrassment. They’ve got to be parked somewhere out of harm’s way—the order’s been given now we must take as many prisoners as we can—till the die-hard resisters and the snipers who’ve holed up behind rubble and in ruined buildings can be dealt with. That’s what Snowy’s sent to do, pick off snipers—he’s a blanky good shot but yours truly is put on guard duty, the last thing I want to do. I try to argue with the officer but he’s in no mood to listen and so I have to march off with three of our blokes and this column of dejected, ashen-faced Jerries to wait in a safe spot in the fields till the all-clear is given.

I’m simmering with annoyance at the thought I have to play nanny to this bunch while my mates are still out there fighting. That blanky officer knows I’m younger than the others. Less experienced. In his mind that qualifies me for the soft jobs.

Cos the Jerry prisoners are not going to be a problem any time soon. They look exhausted. Broken down. Some of them are wounded but only slightly—the really injured ones have been stretchered off, like our wounded. Their uniforms are dirty, stained, their eyes are empty. Crack Bavarian and Prussian troops were supposed to be stationed here, we were told. Well, these fellas don’t look like crack anything except cracked in spirit. They’ve given up. They don’t look at me but stare at the ground.

Time passes. Dawn breaks, the sun rises, the day advances. Dimly in the town behind us we can hear the occasional crack of a rifle or a burst of machine gun fire but it’s getting fewer. More prisoners join our lot. They all sit there, staring at the ground. I wonder what they’re thinking. Your average Jerry is a fanatic, I’ve read. Thinks his race are supermen. Some supermen this lot! My mind skitters around. If the Jerries hadn’t started the war then I wouldn’t be here. Owl and Blue’d be safe with their families. Snowy would’ve taken up that job as horse trainer, become a big shot. Jamie wouldn’t be dead. Mum would still be alive. I’d have a home. A family. I’d have trained to be a real proper boxer in Melbourne, I’d had offers. I might have a girl too. A pretty thing with long curls like my favourite film star, Lilian Gish. We would go around town with her on my arm and go to restaurants and the picture theatre and on Melbourne Cup Day we’d go to the races with Mum and Jamie down from the country, and we’d pick the winner. Which would be the horse Snowy had trained. We’d win big, there’d be champagne and cake and everything would be..

‘What the blanky blanky are you doing?’ hisses a voice in my ear. It’s Stevie, the one in charge of guard duty. ‘Keep yer eyes open, mate.’

Eh? What’s he talking about? I’ve not been asleep. I glare at him but he doesn’t care. ‘Get up, have a walk around,’ he orders, as though he’s an officer or somethin’. Which he isn’t, just some cocky from way out in the Mallee.

I shrug to show much I give about his orders but I get up anyway because it doesn’t look good in front of the prisoners to be arguing. I walk up and down and as I do I happen to see one of the prisoners staring at me. He’s small and dark and though he has a little moustache it’s clear he’s pretty young. I give him a glare to let him know I’m watching him and he better not be up to any tricks but he gives me this little gesture which looks like he’s waving me over. You have to be joking. If I’m not taking orders from some Mallee cocky, I’m sure not taking any from a blanky Fritz.

I see his mouth form a word. Please. Not bitte, which I know is German for please, but the good old English please. The magic word, Mum always said. What’s the magic word, boys? she’d say to Jamie and me.

‘Yeah, what?’ I say.

‘Please,’ he says, ‘will you come here? ‘

I look at Stevie. He shrugs. Go ahead.

I go over to the bloke. ‘What’d you want?’ I say, roughly.

For answer, he reaches inside his uniform. I don’t stop to think. I leap at him, grab him by the throat, my hands tighten around it, I’m going to choke the life out of him. Then I’m pulled off him and Stevie’s bellowing, ‘Cripes you mad bastard, what are you doin,’ and he’s shoving me away, to sprawl in the grass.

I thought he had a knife, I manage to say but Stevie shakes his head. ‘You’re touched, mate,’ he says, ‘now pull yerself together or yer’ll end up in the clink. Prisoners is prisoners, see, you don’t hurt them, not unless you want our blokes to be hurt too.’

I know that. I know all that. Shame is washing over me in cold crinkles of skin. Jeez, I’m not that sort. Not the kind that would go for an unarmed bloke. I want to explain. That I really thought he had a knife. But I know it wasn’t just that. Owl and Blue are dead and Jamie and Mum and countless many more and for an instant to me that bloke he looked to me like the one who done them all in. I know that’s mad. I know it is, but I hated him more in that moment than I hated the one I’d killed back there, the one with the blue eyes like Jamie’s. I wanted him to pay. I wanted someone to pay. Some bastard Jerry would-be superman. But now I look at the bloke and all I see is a frightened kid trying to look like a man and I feel sick to my stomach.

‘You goin to behave now, cobber?’ asks Stevie, not unkindly, and I nod. ‘Get away over the other side, then,’ he says, and I nod again. I’m about to go when I hesitate. Part of me wants to go to the prisoner and say—what? An apology? That would stick in my craw. No. I can’t say anything. There is nothing to say. I’m turning away when I hear this whisper from him, hoarse, because of his throat which must be sore. ‘It is a letter, yes? For my sister. Will you send it? ‘And he pulls it out of his pocket, and hands it to me.

I stare at him. He looks back. I can’t say what it is he has in his eyes. I can’t read people that well. But our eyes meet, just for that instant. Without a word, I nod, take that letter, and walk away, to the other side of the group of prisoners. There is such an ache in my chest. A feeling that grips me tight, like the killing fury, like the pain of memory. Cripes, it’s too big for me. The pity of it all.