On this page, you’ll find some recipes and food notes extracted from Kate’s notebook, as she wrote them down, during her time in The Paris Cooking School. They are all recipes that are easy to make at home, and are illustrated with photos of the actual dishes. There’s also a shorter page elsewhere on this site which features a simple menu, here.

Copyright Note: All images of the notebook copyright Lorena Carrington, recipes and food photos copyright Sophie Beaumont.

Eggs:

Oeufs mimosa: An easy and impressive entrée or lunch snack!

Boil eggs (one per person) for around 10 mins from the time the water boils. Let cool, then split in two, scoop out the yolks, and set part of the yolk aside (about a third to a half of one yolk, if you are using two eggs). Mash the rest of the yolk in a bowl with a fork, adding a touch of Dijon mustard, a touch of lemon, a dribble of olive oil (or, traditionally, homemade mayonnaise), salt, pepper. Mix everything together and heap the yolk mix into the whites. Press the reserved yolk through a sieve to produce little yellow balls that look like mimosa(wattle) flowers. Place the ‘mimosa’ on top of the yolk mix, then set out on a platter, decorated if you like with herb leaves, and serve. You can vary what you mix the yolks with. Sylvie says you shouldn’t be afraid to experiment!

Piperade: traditional Basque dish, made by Gabi. So for a piperade for 2 people, you need one chopped medium onion, two cloves garlic, three large fresh peeled cooked tomatoes(or a cup of tomato juice, for a quick version), two long pale green peppers, half a red capsicum(both peppers and capsicum need to be cut into strips and cooked in a little olive oil, or roasted, prior to using in the piperade. (Gabi also says her dad sometimes does it without the green peppers, or substitutes green capsicum—but the red capsicum is essential). You also need thyme, a bay leaf, salt, sugar, and piment d’Espelette, and you can also put in strips of Bayonne or Serrano ham if you like. You cook up the chopped onion and garlic in olive oil, add peeled cooked tomatoes or tomato juice plus fried or roasted capsicum and pepper cut into strips, add thyme and one bay leaf, add salt and some sugar to taste(as tomato is acidic and this needs to be more balanced), add chopped ham if you like, and then piment d’Espelette. Then simmer the sauce, covered, for about 20 mins till it’s reduced and become thick. Crack two eggs into a bowl, whip up till frothy, then tip into the pan and stir through till well-cooked. Serve with fresh crusty bread and a salad on the side.

Oeufs en cocotte, a la crème et l’estragon: These are amazingly easy and delicious baked eggs with cream and tarragon, and were made by Sylvie and Damien the first day we were at the School.

You need 2 eggs per person, a ramekin per person, plus some chopped tarragon and some cream (not thickened) plus salt and pepper. Set the oven at 180C. Butter the ramekins, drop in the cream(about 2 two tablespoons to each ramekin) stir in most of the chopped tarragon, salt and pepper, then gently crack two eggs into each ramekin. Finish with the last bit of the tarragon. Prepare a deepish tray with hot water and slide into oven, then put the ramekins gently into the tray. Cook for about 15 minutes, or until eggs are set(you can easily check). Let cool a couple of minutes, then serve with crusty bread!

Soups:

Soupe a l’oseille et a l’ail: This sorrel and garlic soup was made by Anja and Stefan when we had the soup day, and I loved it so much! It’s dead simple too.

For enough soup for 2 people, you need a small handful of sorrel leaves, two large cloves garlic or 3 smaller cloves, butter, 1 cup chicken or vegetable stock (homemade or made from a soup cube, Sylvie says that’s perfectly okay!) plus, optionally, a little cream. Chop the sorrel and toss it quickly in some melted butter over the stove. It will wilt almost immediately. Quickly add the chopped garlic, toss, then add the stock, stir, and let it simmer for about 15-20 mins, then just at the end of the cooking time, add an egg yolk and stir through till it’s spread throughout. You can also add a dash of cream if you like. Serve with croutons or simply crusty bread.

Sylvie says that if you can’t get sorrel, you can use watercress or even chopped rocket instead, and add a squeeze of lemon at the end to reproduce that tangy sorrel taste. Also, you can add chopped spinach to it.

Lettuce and pea soup, that was made by another pair at the school, was another simple one I loved: basically, you just cook the chopped lettuce till it’s wilted, add the fresh peas, salt, pepper, stock, and simmer for 15 minutes or so. Add a bit of cream and chopped mint right at the end.

Ttoro, a Basque fish soup: Gabi gave me this recipe from her family repertoire, it’s absolutely amazing! Sumptuous and takes a bit of time to prepare, but not hard to make. Gabi says it’s kind of similar to bouillabaisse only with very Basque aspects, like capscicums and the Basque spice known as piment d’Espelette. (You can get the actual piment in lots of online shops but if you’re really stuck, you can use hot—but not smoked—paprika). By the way, ‘ttoro’ is pronounced ‘tioro’.

So for two people, you need: two fillets of fish, cut into bite-sized pieces (your choice of fish); 8-10 cooked peeled prawns; two tomatoes, chopped; one red capsicum, chopped; One medium onion, chopped; four cloves garlic, sliced; olive oil; salt; piment d’Espelette or paprika(see what I said above); a bit of any other seafood you fancy: eg mussels, squid, scallops, etc; and 3-4 cups of pre-prepared seafood/fish stock(home made or from stock cubes). So, in a good-sized pan, fry the onions and garlic in olive oil till starting to soften. Add the tomatoes and capsicum, stir, add salt and half a teaspoon of piment d’Espelette or paprika, and leave to cook for about 5-6 mins with lid on. Then pour in the hot stock, and allow to cook at a simmer for a further 5-6 mins, to absorb the flavours. Then add the pieces of raw fish, and cook for 2-3 mins. Add the rest of the seafood, including the prawns. Cook for about another 2-3 mins, at a simmer. Sprinkle more piment d’Espelette in. Taste, add salt if necessary. Then take off stove, and serve with crusty bread! She says the soup also keeps well overnight in the fridge—you can eat the delicious leftover soup, heated up, the next day!

Salads and cold vegs: Before I forget, here’s the recipe for vinaigrette, that lovely tangy dressing the French use in pretty much all salads, from the most basic tossing of lettuce to the most elaborate mix. The basic one is just virgin olive oil mixed with red or white wine vinegar, salt, pepper, and a little mustard(you can use basic Dijon mustard, or those with added herbs, wine, etc). Obviously you have more oil than vinegar 😊 it’s like 2 or 3 parts oil with one part vinegar. It’s got to taste tangy, not oily though. Sylvie also includes a little grated garlic and chopped tarragon in hers, when tarragon is in season that is. Otherwise she uses tarragon mustard. Salads by the way are an indispensable part of the French meal, from the simplest green salad(which usually would be served after the main course, as a kind of ‘palate cleanser’ between the main course and the cheese and/or dessert) to elaborate ones which might be served as an entrée or as a single lunch dish. But there’s also other cold veg dishes with vinaigrette which are popular.

Asperges a la vinaigrette: Misaki and I made asparagus vinaigrette for the final group lunch, ultra easy and delish! Take a bunch of fresh green asparagus, steam for about 3-4 minutes, let cool. Arrange on a plate, drizzle vinaigrette over it. Et voila! You can also make poireaux(leeks) a la vinaigrette—a classic French dish!– in the same sort of way, only you don’t steam the leeks, you toss them in hot oil, then add water to cover and cook till tender(then cool before adding the vinaigrette). Also, you can have simple boiled artichokes that you then simply serve with vinaigrette on the side. Everyone just takes an artichoke, peels off each leaf, dipping the soft end into the vinaigrette, eating that and discarding the rest, until you come to the wonderful heart that you can eat in its entirety!

Salade de chevre chaud et d’epinards: Warm goat cheese and spinach salad: Very simple and awesome as an entrée or a lunch dish. For two people, a handful of spinach, butter, a bit crushed garlic, salt, pepper, and fresh(ie not hard) goat cheese, plus two slices of bread (a split piece of baguette is good). Cook the spinach in a bit of butter(and just a drop of water) till wilted. Add a little vinaigrette and a small amount of honey. Toast the bread, put the dressed spinach on top, plus a good slice of goat cheese, and slide into the oven on a tray for just 5 mins-7 mins. Take out and eat!

Salade Composée: Just had to put a note about these because they are real classics that you see in lots of cafes and restaurants in Paris, and apparently all over France. They make fantastic lunches. Basically, it means a mixed salad with lots of different things in it, not tossed in a bowl but arranged on an individual plate so you can see all the different ingredients in it. They look wonderful and taste wonderful! Most have a base of a mix of greens and are dressed with vinaigrette but others might have mayonnaise or other dressing. The extras will include meat, eggs, fish, a whole variety of things! In France you find all types, for example, the ‘Norwegian’ is with smoked salmon, herrings, green lettuce, boiled eggs, and more; a ‘Gascon’ has the south west specialities of foie gras and duck slices; a Basque one might have Bayonne ham and peppers; a Niçoise(the most well known outside of France) tuna, anchovies eggs, etc. You can also have fantastic vegetarian ones with cheese as the centrepiece, and a vegan one might have roasted eggplant and tomato featured with the greens. The possibilities are endless! I’m definitely going to create my own, based on what I learned at the School.

Cooked vegs:

The secret to cooking vegs the French way is simply this: don’t cook them too much! Everything needs to be tender but never mushy. Also, another secret: cook seasonally! Because we were in Paris in spring, we pretty much used only spring vegs from the markets. In Australia of course because of all the different climates we can get many vegs pretty much any time, but still there are some that you can’t, like broad beans, asparagus, artichokes etc, which are all seasonal. And it’s hard to find new potatoes (except maybe in Tasmania, one of my friends who lives there says—they do honour to spuds in our island state!) Anyway, here are a just a few of the many ideas I picked up from Paris. Any of them can be used as centrepieces for vegetarian meals, by the way (you can also make them vegan if you omit the butter and replace with olive oil)

Here’s a simple and succulent way to cook artichoke hearts, with butter and garlic. Sylvie says it’s best done with fresh, young, small artichokes; you boil them till tender, then discard all the leaves except a few soft ones close to the heart, cut off the tips of those leaves, then cut in half the hearts with their attendant leaves, and toss them for a couple of minutes in butter, in a pan over the stove, adding crushed garlic, and a sprinkle of herbs(thyme is good) at the end. You can serve warm or cold. But I loved them warm especially! And you can add other things to the artichoke hearts if you want, like mushrooms, which Anja and Stefan did one time. Artichokes are also great made into a pate: you just boil up a few young artichokes(not too huge!), cool till easy to handle, then discard all the leaves except for the very soft ones around the heart, cut off any spiky bits on top of those leaves, then chop the artichokes into small pieces and put them, chopped red onion, chopped garlic, a bit of olive oil (say a teaspooon), salt, pepper and some sour cream(say a teaspoon or two), then whizz up together in a blender till it becomes a paste. Taste, and if needed, add a bit of oil or sour cream. Put in fridge to cool for a few hours, serve with crackers.

Broad beans are versatile! Take young beans, cook them in a little butter and water and use them in salads, as accompaniments to mains)as with the duck confit and broad bean dish Misaki and I made, where we positioned the warm confit on top of the cooked beans and simply sprinkled a bit of thyme and garlic on them. And peas—fresh peas!—are absolutely awesome and can make a centrepiece of a meal in themselves, too. Also—many French people love those big fat white asparagus—but me, I much prefer the thinner green variety 😊

Choose small vegs if you can—especially with things like potatoes, carrots, leeks etc. They taste better and are easier to cook. But you can do great things even with big old vegs: French country people especially are thrifty, Sylvie told us, and hate wasting food. So for instance with big fat spuds, you can make great chips from them (essential for steak frites!), parboiling the spuds first then cutting into largeish slices and shallow frying in hot oil (canola or sunflower) till you get a gorgeous crisp golden exterior and a melt in the mouth soft interior. Or you can cut the potatoes in slices and layer them in a pan with a little oil, stir around, add some stock (chicken or veg), salt and pepper to taste, cover and leave to simmer for about 15-20 mins or until tender and most of the liquid has drained off, then add a sprinkle of herbs and serve. Goes well with most meats and fish, or with other veg dishes.

A little note about herbs, spices, onions and garlic: French cooking frequently features herbs, especially parsley, thyme, rosemary, sage, tarragon, and bay leaves, but also mint, dill and chervil. There’s a thing they call ‘bouquet garni’, which you can buy in shops, or create your own: a mix of herbs in little cloth bags, these days, Sylvie says, you can find others with different mixes of herbs. You often find mention of ‘bouquet garni’ in traditional French recipes. But if you find herbs a lot in classic French cooking, spices aren’t present as much, apart from cinnamon and nutmeg. And of course there’s the only real French-grown spice, which is actually from the Basque country: piment d’Espelette, which is a fruity, fragrant red powder made from long red peppers grown exclusively in the area around the picturesque small Basque town of Espelette. It has a mildly spicy, very aromatic flavour which goes well with all kinds of things. Meanwhile garlic and onions of course are huge staples of French cooking, and are highly regarded as flavourings. In the markets in the spring, you can find delicious new garlic, which look like miniature leeks—the bulb hasn’t fully formed and the taste is more subtle than fully mature garlic but still distinctive. It’s lovely stuff sliced thinly in salads, in sauces and soups.

Le pain: a note on bread

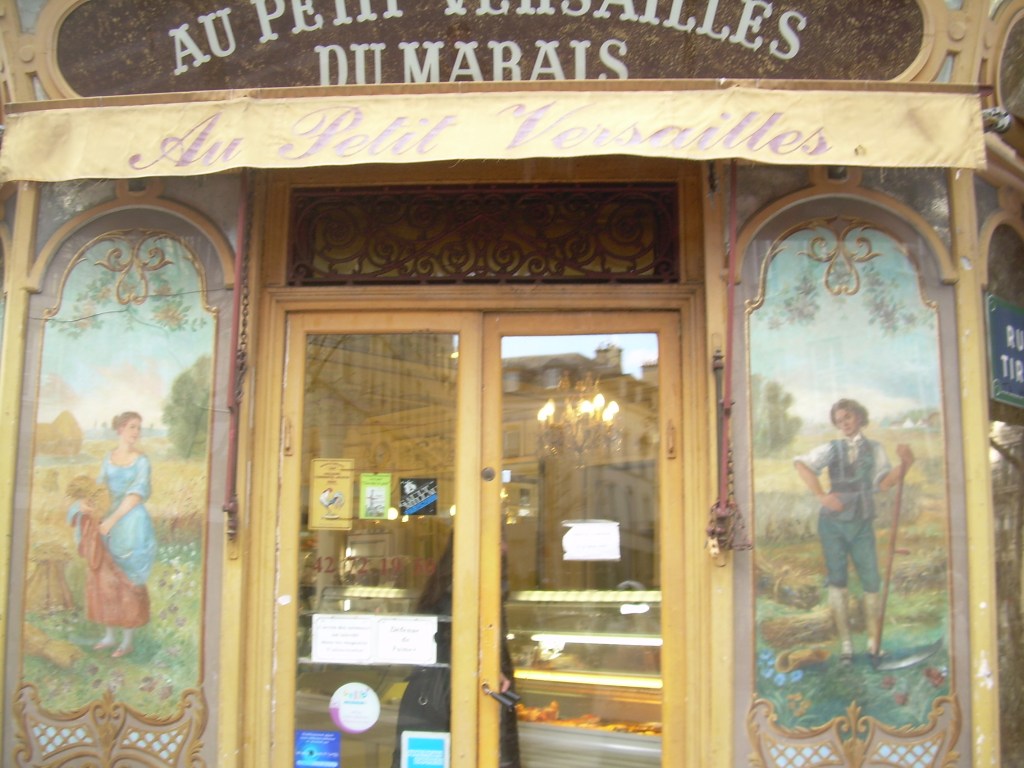

I loved going to our local neighbourhood boulangerie (bakery) in Paris to pick up bread fresh every morning for the day. Bread (le pain) is an indispensable part of every French meal, served at breakfast of course but also at other meals to mop up sauces, push food onto forks, served with cheese, etc etc! The classic baguette and its several versions (such as ficelle, or string, the small thin variety of baguette, or baguette tradition, made with sourdough) is well known of course but there’s also ‘pain de campagne‘ a heartier sort of bread that keeps quite well (unlike the baguette, which basically should be eaten on the day you buy it, which is ideally the day it’s been made!) And there are also other grain varieties, such as seigle (rye) and sarrasin(buckwheat) etc etc. Choice is up to you!

Fish and seafood

Okay, so fish and seafood are really big things in France. People cook them in all sorts of ways, and each region has their own ways of doing it. Mostly, fish is cooked simply, served quickly too, with a light and delicious sauce or simply with salt and lemon( for example, grilled sardines). We made a few of these fishy delights, like the dish that Ethan and I made one time, paired with the sauce that I learned from Annick who came to demonstrate fish dishes to us(and which Arnaud and I made later, on the boat). So you take two decent fillets of fish–grill one of them, roast the other, then serve them on top of each other, with a sauce made with chopped onions cooked in butter, to which you add a touch of white wine and simmer till fairly thick, then off the stove, add a touch of lemon and chopped shallots. It’s divine and super easy! What fish to use? Well, it looks great(and tastes good too) if you use say a white fish and a pink one, eg trout or salmon, but it’s really up to you, that’s the beauty of it! Another fabulously simple fish dish is one Anja and Stefan made for the final group lunch: trout with almonds. You take a (river) trout, dip it first in milk then in salted and peppered flour, pan-fry it on both sides for a few minutes with a little oil, take it out of the pan and lay it on a serving platter or dish. Drain the cooking juices, add a bit of butter to the pan, and toast a handful of flaked almonds in it for 2 mins, stirring constantly. Slip the toasted almonds onto the trout, and serve with potatoes, either small new ones or those braised ones I described earlier, which work well. You can vary the recipe by using whole almonds, caramelising them with sugar and a little water in a pan, and then, when cool, scattering over the cooked fish.

I’ve already written down Gabi’s Basque soup, but here’s a quick description of another fish and seafood dish from that region, which she and Pete made for that final group lunch, only it’s more of a one-pot stew. It’s called merlu koskera. So for 2 people, she says, you take a couple of pieces of white fish (the original recipe is for cod or hake but you can also use snapper or other sorts of dense-fleshed white fish and in fact you can also use other dense-fleshed fish, such as tuna). You take steamed asparagus(the green sort, haha), just-cooked peas or broad beans or spinach or whatever else you have to hand. You take cooked mussels or prawns or whatever you’d like in terms of seafood, plus a couple of hard-boiled eggs, and in a big pan, you put in some olive oil, put in the fish, fry on both sides, then add the vegs, add some seafood/fish stock to make it bubble, add salt and piment d’Espelette(yes, that again, you can’t get away from it, in Basque cooking) simmer gently, add the seafood you want to add, simmer again, just a few minutes. And serve with plain boiled rice or bread. It’s a spring dish so includes spring vegs, but I don’t see why you can’t make it with other vegs in other seasons.

Poultry and meat

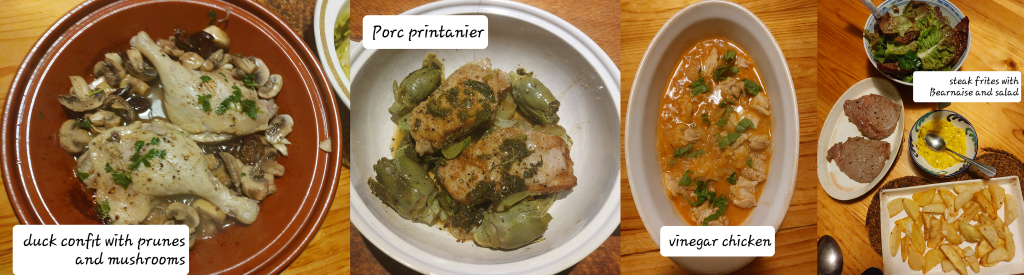

Poulet au vinaigre (vinegar chicken)

This is something that Gabi told me about—Max made it for her. It sounds super easy and utterly delicious! You need chicken thighs (one for each person), one medium onion, 2 cloves garlic, 30 g salted butter, salt, pepper, water. That’s for the basic preparation. Then for a dish that will serve up to 4 people (adjust as necessary), for the sauce you also need 4 tablespoons vinegar(white wine or cider vinegar is best) 1 tablespoon Dijon mustard, 1 tablespoon tomato puree, 3 tablespoons dry white wine, and 3 tablespoons cream (cream is optional, Gabi says). Cut the chicken into pieces(not too small, not too big), chop the onion and garlic, and put onion, garlic and chicken in a pan over the stove, with the butter. Stir a few times till starting to colour. Add salt and pepper to taste and enough water to just about cover the chicken pieces. Simmer gently for about 20 minutes, making sure the juice doesn’t all disappear but also not keeping it too liquid. Add the vinegar, stir. In a separate cup or bowl, mix the wine, mustard and tomato puree, stir till well-blended, then add to the vinegar chicken mix. Simmer for 3-4 minutes, then spoon in the cream (if you are using it), stir, let it simmer another minute before turning off the heat. Serve with plain rice or plain boiled potatoes(delicious with new potatoes!)

Confit de canard aux prunes: Something that comes out of south-west France, where Sylvie originally comes from: it’s a great and easy way to cook duck confit, accompanied by a delicious prune sauce. First you cook the duck confit in its own juices in a frying pan. As confit is already-cooked you only have to cook it for say 15-20 minutes. Add salt and pepper, sliced onions, then take some good-quality plump prunes, chop them and add to the pan along with a dash of cognac or Armagnac (or other brandy) and cook for another 5 mins more. Serve in its sauce, with bread and a side salad. Deliciously simple! You can vary it by adding mushrooms to the pan as well.

Porc printanier: This is a lovely quick and delicious springtime dish Damien showed us. For two people you need two good pork pieces that have some fat (or they won’t be tender)—for example small pork chops, slices of pork shoulder, boneless pork roast slices or pork scotch fillet is good—1/2 cup white wine, a few sorrel leaves, 1 large onion or 2 small ones, some artichoke hearts (fresh if possible), salt pepper, garlic. Shallow fry the pork on both sides, take out of pan to rest, then fry the onions in butter, add the sorrel, artichokes, garlic, then after the onions are soft, put the pork back in, salt and pepper, cook for a few minutes, add white wine and simmer, covered, for about 15 minutes more. Serve with boiled and buttered potatoes on the side or just with fresh bread.

Bearnaise sauce for steak+frites: couldn’t go past this classic! In France quite often steak frites is made not with fillet or rump but with ‘bavette’ or skirt steak, which you can find in Australia(and other countries too) just ask your butcher. It’s a very tasty cut and can be as tender as those other steaks, plus it’s quite a bit cheaper! You just have to pound it a bit first, before cooking. But of course if you want you can use fillet or rump steak instead. And in terms of how you cook a steak, ‘bleu’ or else ‘saignant’, that is, respectively, ‘blue’ or ‘rare’ is how it’s often liked in France, but of course you can also have it ‘À point’ ie medium rare, or bien cuit, well-cooked. The ‘frites’, ie chips, are usually chunky (you can also get thinner chips, called ‘pommes allumettes’ but in my experience they are rarely served with steak). But steak+frites is absolutely inseparable from a tangy Béarnaise sauce, so here’s a quick version that never fails, Sylvie told us! Take a small onion or half a medium one, chop it into small pieces. Put it in a small saucepan with one and a half tablespoons of vinegar(white wine or cider vinegar is best). Simmer on the stove till the vinegar has all been absorbed into the onion. Meanwhile boil some water in another pan. Crack an egg, keeping only the yolk. Cut about 50-60 g butter. Put the onion/vinegar pan over the pan of boiling water, tip the egg yolk into the vinegar/onion mix, stir quickly, it will thicken almost at once. Put the butter into the mix, in small pieces, stirring well as you go, till it blends well together and produces a thick shiny sauce. Take the pan off the heat, add salt and pepper and some chopped herbs if you want (tarragon or thyme). And that’s it!

Cheese:

I’m not even going to try to describe the hundreds of different cheeses there are in France, just to say that in a meal, French people always eat the cheese before the dessert (and after the salad, if you are having one then), and often you change what wine you drink at that point. A French cheese platter can be just a simple presentation of say three cheeses of different types, or more elaborate. And you always eat cheese with bread—crackers are for when you have cheese as an aperitif, maybe with charcuterie as well. (By the way, charcuterie—salamis, ham, etc—is usually reserved for aperitifs, entrees or for lunch. Sausages of course are different.)

Les douceurs: Desserts and cakes

There are lots and lots of desserts and cakes I could include but I don’t have the space, so I’m only going to concentrate on five, which I know how to make and which can be quickly made. The desserts are both cold ones: a divine chocolate mousse and a luscious icecream. The cakes are what you might call home classics, easily cooked at home. Sylvie says that even good home bakers prefer to leave it up to patisseries to make the kind of cakes you find, well, in patisseries! She said that in her family on Sundays the cake had usually come fresh out of the neighbourhood baker/patisserie, and that was the case for many people all over France, it’s a bit of a tradition in fact, no-one feels ashamed of outsourcing dessert. And often on weekdays the meal will finish with cheese and a piece of fruit, not dessert as such. But that doesn’t mean people don’t make cakes at home: they certainly do, and here are three that we made during the School.

A simple, and beloved cake in France is the Quatre-Quarts. Quatre-quarts means four-quarters, so it’s basically a cake made of four main ingredients, each of equal weight. And it’s very simple to make! You take 2 large eggs or 3 medium-sized ones, 150g castor sugar, (fine white sugar)150g soft unsalted butter, 150 g self-raising flour, 2 heaped tablespoons ground almonds and the finely-grated zest of 1 lemon or orange OR a little vanilla essence. Heat the oven to 180 degrees C. Then you beat the eggs, sugar and flavouring together until pale and a little frothy. Put the butter in a round cake tin and heat it in the oven till almost melted. Swirl to coat the tin lightly with butter, then pour the melted butter into the egg mixture a little at a time, whisking till completely blended. Sift the flour over the egg and butter mixture, a little at a time, then fold it in gently with a metal spoon. Now mix in the ground almonds. Dust the buttered tin with a little flour (or use baking paper if you wish), pour in the cake mixture and bake in the oven for a good 35-40 minutes. If the top browns too quickly, cover it with a piece of foil. To check that the cake is cooked, insert a skewer or small knife — if it comes out clean, the cake is cooked. Turn the cake out on a rack and cool. Decorate if you wish, though it can be eaten plain. The cake keeps well for a few days too. Beloved of French schoolkids as an after school snack–great for lunchboxes too!

Okay, so now the Pithiviers pie. (Sylvie told us a funny story about that one, mishearing the name of it as a kid!) The Pithiviers originates in the town with the same name, in northern France, but it’s spread all over the country. And it’s an absolute classic of home baking. Now normally it’s made with puff pastry, and certainly that’s the classic way of doing it (and you can use bought puff pastry no problem) but Sylvie showed us a different, easier home-made method that doesn’t involve all the palaver of making puff pastry and she said it has the same delicious texture as ‘normal’ puff pastry but is easier, like shortcrust pastry. So, you need: for the pastry, 150 g plain flour; 50 g cold unsalted butter; crème fraiche(sour cream)or buttermilk. For the filling: 125 g almond meal; 50 g castor sugar; 1 egg yolk; about 30-40 g softened unsalted butter; drop vanilla essence. Optional: drop armagnac or cognac. (You can also, instead of almond meal, use hazelnut meal, and mix it with melted chocolate.) For glaze of the pie: 1 egg yolk. To make the pastry, cut the butter into pieces and rub through flour till mixture ressembles fine breadcrumbs. Add enough sour cream or buttermilk to make a soft but not sticky dough. Set aside to rest in a cool place while you make the filling. Mix almond meal, sugar, egg yolk, softened butter and vanilla essence in a bowl, and cognac/Armagnac brandy too if you wish. It needs to be fairly soft but holding together well, a bit softer than bought marzipan. Then divide the pastry in slightly unequal halves(the bit for base and sides needs to be a bit bigger than the bit for the top. ) Roll out each part. Lay the base and sides part in a buttered pie dish and then spread the almond mixture over it to cover it to every corner. Place the pie lid on top of that, pinch sides together. Then paint top with egg yolk and score it with a sharp knife taking care not to go right through top (it’s just for decoration really.) Bake in a moderate oven, around 180C, for about 40 minutes. You can serve warm or let it cool down. And it’s just as good the next day(if there are leftovers of course!)

Tarte Tatin!

This glorious upside down apple tart was the invention of the Tatin sisters, Caroline and Stéphanie, who had a restaurant in the Sologne region at the end of the 19th century. The legend goes that it was as a result of a mistake by Stéphanie—burning the caramelised apples for a ‘normal’ tart, then hastily putting the pastry on top to hide it—that the famous Tatin tart was born. (Although in my opinion that’s hard to believe!) Anyway, Sylvie told us that the ‘mistake’ proved so delicious that people came from far and wide to eat the Tatin tart—and the sisters became famous too. They were even invited to the house in Giverny of the great Impressionist painter Claude Monet, who was a great gourmet, and they wrote down their own recipe for him—or rather so that his cook could make it even after they’d gone home! I love that image—the great artist and the great cooks, bonding over a buttery caramelised upside down apple tart! Anyway, okay, so here’s how Sylvie showed us how to make it(it’s her adapted version): Firstly, take a deep round metal tin that can go on the hot plate as well as in the oven. That’s because the apples will be cooked in it first before the pastry goes on top. (Sylvie says you can even use a cast iron frying pan, as it can go in the oven, if you take off the handle) Make the pastry in the same way as for the Pithiviers pie, and set aside to rest in the fridge. Meanwhile peel, core and cut two-three crisp apples(depends on their size) into segments(either halves or quarters) and put them upside down in the tin on the stove, with a chunk of unsalted butter(say around 60-80 g)and around 90 g of castor sugar. Cook over a moderate to high heat till the apples are caramelised and golden and soft(but not mushy!) Watch carefully and stir frequently as you don’t want it to burn(no matter what Stéphanie did 😊) Take off the stove, roll out the pastry, put it on top of the apples and pop straight away into a pre-heated oven(180 degrees C) To serve, turn tin upside down onto a plate so the beautiful sticky golden apples appear on top–or you can serve as is in the tin, with the pastry on top. Up to you (though I think turning it upside down looks more spectacular!) Serve with crème Chantilly (ie whipped cream, with a little sugar and a flavouring such as vanilla. And by the way use only pure cream, not thickened cream)

Two cold desserts:

Simple chocolate mousse

Damien taught us this one, and it works perfectly every time. You take 150 g dark chocolate, 2 eggs, 60 g unsalted butter, and 1-2 tablespoons castor sugar. Separate the eggs first. Then cut the chocolate up, and put it and the butter in a small saucepan, over a pan of boiling water, on the stove. Once it’s melted together, add the egg yolks, stir till fully incorporated, then take off the stove. Leave to cool for a while, then beat up the egg whites with the sugar till soft peaks form. Fold into the chocolate mixture, gently, till it’s al mixed in, then put into individual bowls/ramekins or one larger bowl if you prefer. Put it in the fridge for at least 3 hours or even overnight, then serve. You can also add a dollop of crème Chantilly(whipped cream) on top, for decoration.

The Writer’s Icecream: this is my name for an icecream recipe that Sylvie told us she picked up from a writer she met at a book launch once. It’s dead simple. So you take two eggs, separate them, and beat the whites with sugar(about four tablespoons) till they are light and form in stiff peaks, like for meringue. You then whip up some cream (pure whipping cream, not thickened or double cream) with a bit of sugar (say two tablespoons), fold the egg white mix into the whipped cream, add a couple of drops of vanilla essence, or melted chocolate, or coffee, or a mix of things–as long as you don’t add anything water-based to it, or fresh fruit—though jam is okay. You can even make layered ‘Neapolitan’ style icecream with one layer of vanilla icecream, one with melted chocolate, and one with strawberry or raspberry jam. Then you put your mixture in the freezer for several hours or preferably overnight., And there! Perfect icecream, that never fails and never crystallises…as long as you remember the rule about no water-based additions or fresh fruit 🙂 For a variant called a ‘parfait’ you can also beat up the egg yolks with sugar and add them to the egg white mix and cream before putting the whole thing in the freezer: that makes a yellow, very creamy kind of icecream.

(If you don’t do that, Sylvie says, you can use the reserved egg yolks to make mayonnaise, which is simple too, just oil slowly trickled into the beaten egg yolk until it goes thick and smooth, then add salt, pepper, herbs and even roasted garlic, if you want!)